Keywords: thomas edison

Source: Wikipedia

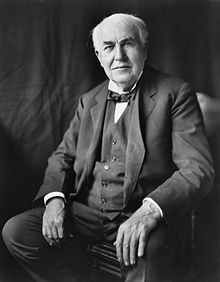

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. Dubbed "The Wizard of Menlo Park",[1] he was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of mass production

and large-scale teamwork to the process of invention, and because of

that, he is often credited with the creation of the first industrial research laboratory.[2]

Edison is the fourth most prolific inventor in history, holding 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as many patents in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. He is credited with numerous inventions that contributed to mass communication and, in particular, telecommunications. These included a stock ticker, a mechanical vote recorder, a battery for an electric car, electrical power, recorded music and motion pictures.

His advanced work in these fields was an outgrowth of his early career as a telegraph operator. Edison developed a system of electric-power generation and distribution[3] to homes, businesses, and factories – a crucial development in the modern industrialized world. His first power station was on Pearl Street in Manhattan, New York.[3]

In school, the young Edison's mind often wandered, and his teacher, the Reverend Engle, was overheard calling him "addled". This ended Edison's three months of official schooling. Edison recalled later, "My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me; and I felt I had something to live for, someone I must not disappoint." His mother taught him at home.[7] Much of his education came from reading R.G. Parker's School of Natural Philosophy.

Edison developed hearing problems at an early age. The cause of his deafness has been attributed to a bout of scarlet fever during childhood and recurring untreated middle-ear infections. Around the middle of his career, Edison attributed the hearing impairment to being struck on the ears by a train conductor when his chemical laboratory in a boxcar caught fire and he was thrown off the train in Smiths Creek, Michigan, along with his apparatus and chemicals. In his later years, he modified the story to say the injury occurred when the conductor, in helping him onto a moving train, lifted him by the ears.[8][9]

Edison's family moved to Port Huron, Michigan, after the railroad bypassed Milan in 1854 and business declined;[10] his life there was bittersweet. Edison sold candy and newspapers on trains running from Port Huron to Detroit, and sold vegetables to supplement his income. He also studied qualitative analysis, and conducted chemical experiments on the train until an accident prohibited further work of the kind.[11]

Edison obtained the exclusive right to sell newspapers on the road, and, with the aid of four assistants, he set in type and printed the Grand Trunk Herald, which he sold with his other papers.[11] This began Edison's long streak of entrepreneurial ventures, as he discovered his talents as a businessman. These talents eventually led him to found 14 companies, including General Electric, which is still one of the largest publicly traded companies in the world.[12][13]

In 1866, at the age of 19, Edison moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where, as an employee of Western Union, he worked the Associated Press bureau news wire. Edison requested the night shift, which allowed him plenty of time to spend at his two favorite pastimes—reading and experimenting. Eventually, the latter pre-occupation cost him his job. One night in 1867, he was working with a lead–acid battery when he spilled sulfuric acid onto the floor. It ran between the floorboards and onto his boss's desk below. The next morning Edison was fired.[15]

One of his mentors during those early years was a fellow telegrapher and inventor named Franklin Leonard Pope, who allowed the impoverished youth to live and work in the basement of his Elizabeth, New Jersey home. Some of Edison's earliest inventions were related to telegraphy, including a stock ticker. His first patent was for the electric vote recorder, (U.S. Patent 90,646),[16] which was granted on June 1, 1869.[17]

On February 24, 1886, at the age of thirty-nine, Edison married the 20-year-old Mina Miller (1866–1947) in Akron, Ohio.[23] She was the daughter of the inventor Lewis Miller, co-founder of the Chautauqua Institution and a benefactor of Methodist charities. They also had three children together:

Edison began his career as an inventor in Newark, New Jersey,

with the automatic repeater and his other improved telegraphic devices,

but the invention that first gained him notice was the phonograph in 1877.[29]

This accomplishment was so unexpected by the public at large as to

appear almost magical. Edison became known as "The Wizard of Menlo

Park," New Jersey.[1]

His first phonograph recorded on tinfoil around a grooved cylinder, but had poor sound quality and the recordings could be played only a few times. In the 1880s, a redesigned model using wax-coated cardboard cylinders was produced by Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, and Charles Tainter. This was one reason that Thomas Edison continued work on his own "Perfected Phonograph."

Edison's major innovation was the first industrial research lab, which was built in Menlo Park, New Jersey. It was built with the funds from the sale of Edison's quadruplex telegraph.

After his demonstration of the telegraph, Edison was not sure that his

original plan to sell it for $4,000 to $5,000 was right, so he asked

Western Union to make a bid. He was surprised to hear them offer

$10,000, ($202,000 USD 2010), which he gratefully accepted.[30]

The quadruplex telegraph was Edison's first big financial success, and Menlo Park became the first institution set up with the specific purpose of producing constant technological innovation and improvement. Edison was legally attributed with most of the inventions produced there, though many employees carried out research and development under his direction. His staff was generally told to carry out his directions in conducting research, and he drove them hard to produce results.

William Joseph Hammer, a consulting electrical engineer, began his duties as a laboratory assistant to Edison in December 1879. He assisted in experiments on the telephone, phonograph, electric railway, iron ore separator, electric lighting, and other developing inventions. However, Hammer worked primarily on the incandescent electric lamp and was put in charge of tests and records on that device. In 1880, he was appointed chief engineer of the Edison Lamp Works. In his first year, the plant under General Manager Francis Robbins Upton turned out 50,000 lamps. According to Edison, Hammer was "a pioneer of incandescent electric lighting".[31] Frank J. Sprague, a competent mathematician and former naval officer, was recruited by Edward H. Johnson and joined the Edison organization in 1883. One of Sprague's contributions to the Edison Laboratory at Menlo Park was to expand Edison's mathematical methods. Despite the common belief that Edison did not use mathematics, analysis of his notebooks reveal that he was an astute user of mathematical analysis conducted by his assistants such as Francis Robbins Upton, for example, determining the critical parameters of his electric lighting system including lamp resistance by an analysis of Ohm's Law, Joule's Law and economics.[32]

Nearly all of Edison's patents were utility patents, which were protected for a 17-year period and included inventions or processes that are electrical, mechanical, or chemical in nature. About a dozen were design patents, which protect an ornamental design for up to a 14-year period. As in most patents, the inventions he described were improvements over prior art. The phonograph patent, in contrast, was unprecedented as describing the first device to record and reproduce sounds.[33]

In just over a decade, Edison's Menlo Park laboratory had expanded to occupy two city blocks. Edison said he wanted the lab to have "a stock of almost every conceivable material".[34] A newspaper article printed in 1887 reveals the seriousness of his claim, stating the lab contained "eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels ... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark's teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell ... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock's tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores ..." and the list goes on.[35]

Over his desk, Edison displayed a placard with Sir Joshua Reynolds' famous quotation: "There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.[36] This slogan was reputedly posted at several other locations throughout the facility.

With Menlo Park, Edison had created the first industrial laboratory concerned with creating knowledge and then controlling its application.[37]

Edison did not invent the first electric light bulb, but instead invented the first commercially practical incandescent light.[38] Many earlier inventors had previously devised incandescent lamps, including Alessandro Volta's demonstration of a glowing wire in 1800 and inventions by Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans. Others who developed early and commercially impractical incandescent electric lamps included Humphry Davy, James Bowman Lindsay, Moses G. Farmer,[39] William E. Sawyer, Joseph Swan and Heinrich Göbel. Some of these early bulbs had such flaws as an extremely short life, high expense to produce, and high electric current drawn, making them difficult to apply on a large scale commercially.[40]

After many experiments with platinum and other metal filaments, Edison returned to a carbon filament.[inconsistent] The first successful test was on October 22, 1879;[41] it lasted 13.5 hours.[42] Edison continued to improve this design and by November 4, 1879, filed for U.S. patent 223,898 (granted on January 27, 1880) for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires".[43]

Although the patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament including "cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways",[43] it was not until several months after the patent was granted that Edison and his team discovered a carbonized bamboo filament that could last over 1,200 hours. The idea of using this particular raw material originated from Edison's recalling his examination of a few threads from a bamboo fishing pole while relaxing on the shore of Battle Lake in the present-day state of Wyoming, where he and other members of a scientific team had traveled so that they could clearly observe a total eclipse of the sun on July 29, 1878, from the Continental Divide.[44]

In 1878, Edison formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Edison made the first public demonstration of his incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. It was during this time that he said: "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles."[45]

Lewis Latimer joined the Edison Electric Light Company in 1884. Latimer had received a patent in January 1881 for the "Process of Manufacturing Carbons", an improved method for the production of carbon filaments for lightbulbs. Latimer worked as an engineer, a draftsman and an expert witness in patent litigation on electric lights.[46]

George Westinghouse's company bought Philip Diehl's competing induction lamp patent rights (1882) for $25,000, forcing the holders of the Edison patent to charge a more reasonable rate for the use of the Edison patent rights and lowering the price of the electric lamp.[47]

On October 8, 1883, the US patent office ruled that Edison's patent was based on the work of William Sawyer and was therefore invalid. Litigation continued for nearly six years, until October 6, 1889, when a judge ruled that Edison's electric-light improvement claim for "a filament of carbon of high resistance" was valid.[48] To avoid a possible court battle with Joseph Swan, whose British patent had been awarded a year before Edison's, he and Swan formed a joint company called Ediswan to manufacture and market the invention in Britain.

Mahen Theatre in Brno (in what is now the Czech Republic) was the first public building in the world to use Edison's electric lamps, with the installation supervised by Edison's assistant in the invention of the lamp, Francis Jehl.[49] In September 2010, a sculpture of three giant light bulbs was erected in Brno, in front of the theatre.[50]

Earlier in the year, in January 1882, he had switched on the first steam-generating power station at Holborn Viaduct in London. The DC supply system provided electricity supplies to street lamps and several private dwellings within a short distance of the station. On January 19, 1883, the first standardized incandescent electric lighting system employing overhead wires began service in Roselle, New Jersey.

Nikola Tesla worked for Edison for two years at the Continental Edison Company in France starting in 1882,[52] and another year at the Edison Machine Works in New York City[53] ending in a disagreement over pay.

Edison's true success, like that of his friend Henry Ford, was in his ability to maximize profits through establishment of mass-production systems and intellectual property rights. George Westinghouse and Edison became adversaries because of Edison's promotion of direct current (DC) for electric power distribution instead of the more easily transmitted alternating current (AC) system promoted by Westinghouse. Unlike DC, AC could be stepped up to very high voltages with transformers, sent over thinner and cheaper wires, and stepped down again at the destination for distribution to users.

In 1887, there were 121 Edison power stations in the United States delivering DC electricity to customers. When the limitations of DC were discussed by the public, Edison launched a propaganda campaign to convince people that AC was far too dangerous to use. The problem with DC was that the power plants could economically deliver DC electricity only to customers within about one and a half miles (about 2.4 km) from the generating station, so that it was suitable only for central business districts. When George Westinghouse suggested using high-voltage AC instead, as it could carry electricity hundreds of miles with marginal loss of power, Edison waged a "War of Currents" to prevent AC from being adopted.

The war against AC led him to become involved in the development and promotion of the electric chair (using AC) as an attempt to portray AC to have greater lethal potential than DC. Edison went on to carry out a brief but intense campaign to ban the use of AC or to limit the allowable voltage for safety purposes. As part of this campaign, Edison's employees publicly electrocuted stray or unwanted animals to demonstrate the dangers of AC;[54][55] alternating electric currents are slightly more dangerous in that frequencies near 60 Hz have a markedly greater potential for inducing fatal "cardiac fibrillation" than do direct currents.[56] On one of the more notable occasions, in 1903, Edison's workers electrocuted Topsy the elephant at Luna Park, near Coney Island, after she had killed several men and her owners wanted her put to death.[57] His company filmed the electrocution.

AC replaced DC in most instances of generation and power distribution, enormously extending the range and improving the efficiency of power distribution. Though widespread use of DC ultimately lost favor for distribution, it exists today primarily in long-distance high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission systems. Low-voltage DC distribution continued to be used in high-density downtown areas for many years but was eventually replaced by AC low-voltage network distribution in many of them.[58]

DC had the advantage that large battery banks could maintain continuous power through brief interruptions of the electric supply from generators and the transmission system. Utilities such as Commonwealth Edison in Chicago had rotary converters or motor-generator sets, which could change DC to AC and AC to various frequencies in the early to mid-20th century. Utilities supplied rectifiers to convert the low voltage AC to DC for such DC loads as elevators, fans and pumps. There were still 1,600 DC customers in downtown New York City as of 2005, and service was finally discontinued only on November 14, 2007.[58] Most subway systems are still powered by direct current.

The fundamental design of Edison's fluoroscope is still in use today, although Edison himself abandoned the project after nearly losing his own eyesight and seriously injuring his assistant, Clarence Dally. Dally had made himself an enthusiastic human guinea pig for the fluoroscopy project and in the process been exposed to a poisonous dose of radiation. He later died of injuries related to the exposure. In 1903, a shaken Edison said "Don't talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them."[59]

On August 9, 1892, Edison received a patent for a two-way telegraph. In April 1896, Thomas Armat's Vitascope, manufactured by the Edison factory and marketed in Edison's name, was used to project motion pictures in public screenings in New York City. Later he exhibited motion pictures with voice soundtrack on cylinder recordings, mechanically synchronized with the film.

Officially the kinetoscope entered Europe when the rich American Businessman Irving T. Bush

(1869–1948) bought from the Continental Commerce Company of Frank Z.

Maguire and Joseph D. Baucus a dozen machines. Bush placed from October

17, 1894, the first kinetoscopes in London. At the same time the French

company Kinétoscope Edison Michel et Alexis Werner bought these machines

for the market in France. In the last three months of 1894, The

Continental Commerce Company sold hundreds of kinetoscopes in Europe

(i.e. the Netherlands and Italy). In Germany and in Austria-Hungary the kinetoscope was introduced by the Deutsche-österreichische-Edison-Kinetoscop Gesellschaft, founded by the Ludwig Stollwerck[62] of the Schokoladen-Süsswarenfabrik Stollwerck & Co of Cologne.

The first kinetoscopes arrived in Belgium at the Fairs in early 1895. The Edison's Kinétoscope Français, a Belgian company, was founded in Brussels on January 15, 1895, with the rights to sell the kinetoscopes in Monaco, France and the French colonies. The main investors in this company were Belgian industrialists.[63]

On May 14, 1895, the Edison's Kinétoscope Belge was founded in Brussels. The businessman Ladislas-Victor Lewitzki, living in London but active in Belgium and France, took the initiative in starting this business. He had contacts with Leon Gaumont and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. In 1898 he also became a shareholder of the Biograph and Mutoscope Company for France.[63]

In 1901, he visited the Sudbury area in Ontario, Canada, as a mining prospector, and is credited with the original discovery of the Falconbridge ore body. His attempts to mine the ore body were not successful, however, and he abandoned his mining claim in 1903.[64] A street in Falconbridge, as well as the Edison Building, which served as the head office of Falconbridge Mines, are named for him.

Other exhibitors similarly routinely copied and exhibited each other's films.[65] To better protect the copyrights on his films, Edison deposited prints of them on long strips of photographic paper with the U.S. copyright office. Many of these paper prints survived longer and in better condition than the actual films of that era.[66]

Edison's favorite movie was The Birth of a Nation. He thought that talkies had "spoiled everything" for him. "There isn't any good acting on the screen. They concentrate on the voice now and have forgotten how to act. I can sense it more than you because I am deaf."[67] His favorite stars were Mary Pickford and Clara Bow.[68]

In 1908, Edison started the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was a conglomerate of nine major film studios (commonly known as the Edison Trust). Thomas Edison was the first honorary fellow of the Acoustical Society of America, which was founded in 1929.

Edison moved from Menlo Park after the death of Mary Stilwell and purchased a home known as "Glenmont" in 1886 as a wedding gift for Mina in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey. In 1885, Thomas Edison bought property in Fort Myers, Florida, and built what was later called Seminole Lodge

as a winter retreat. Edison and his wife Mina spent many winters in

Fort Myers where they recreated and Edison tried to find a domestic

source of natural rubber.

Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, later lived a few hundred feet away from Edison at his winter retreat in Fort Myers, Florida. Edison even contributed technology to the automobile. They were friends until Edison's death.

In 1928, Edison joined the Fort Myers Civitan Club. He believed strongly in the organization, writing that "The Civitan Club is doing things—big things—for the community, state, and nation, and I certainly consider it an honor to be numbered in its ranks."[69] He was an active member in the club until his death, sometimes bringing Henry Ford to the club's meetings.

This fleet of cars would serve commuters in northern New Jersey for the next 54 years until their retirement in 1984. A plaque commemorating Edison's inaugural ride can be seen today in the waiting room of Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken, which is presently operated by New Jersey Transit.[70]

Edison was said to have been influenced by a popular fad diet in his last few years; "the only liquid he consumed was a pint of milk every three hours".[41] He is reported to have believed this diet would restore his health. However, this tale is doubtful. In 1930, the year before Edison died, Mina said in an interview about him, "correct eating is one of his greatest hobbies." She also said that during one of his periodic "great scientific adventures", Edison would be up at 7:00, have breakfast at 8:00, and be rarely home for lunch or dinner, implying that he continued to have all three.[67]

Edison became the owner of his Milan, Ohio, birthplace in 1906. On his last visit, in 1923, he was reportedly shocked to find his old home still lit by lamps and candles.

Thomas Edison died of complications of diabetes on October 18, 1931, in his home, "Glenmont" in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey, which he had purchased in 1886 as a wedding gift for Mina. He is buried behind the home.[71][72]

Edison's last breath is reportedly contained in a test tube at the Henry Ford Museum. Ford reportedly convinced Charles Edison to seal a test tube of air in the inventor's room shortly after his death, as a memento. A plaster death mask was also made.[73]

Mina died in 1947.

Nonviolence was key to Edison's moral views, and when asked to serve as a naval consultant for World War I, he specified he would work only on defensive weapons and later noted, "I am proud of the fact that I never invented weapons to kill." Edison's philosophy of nonviolence extended to animals as well, about which he stated: "Nonviolence leads to the highest ethics, which is the goal of all evolution. Until we stop harming all other living beings, we are still savages."[75] However, he is also notorious for having electrocuted a number of dogs in 1888, both by direct and alternating current, in an attempt to argue that the former (which he had a vested business interest in promoting) was safer than the latter (favored by his rival George Westinghouse).[76]

Edison's success in promoting direct current as less lethal also led to alternating current being used in the electric chair adopted by New York in 1889 as a supposedly humane execution method. Because Westinghouse was angered by the decision, he funded Eighth Amendment-based appeals for inmates set to die in the electric chair, ultimately resulting in Edison providing the generators which powered early electrocutions and testifying successfully on behalf of the state that electrocution was a painless method of execution.[77]

In the same article, he expounded upon the absurdity of a monetary system in which the taxpayer of the United States, in need of a loan, be compelled to pay in return perhaps double the principal, or even greater sums, due to interest. His basic point was that if the Government can produce debt based money, it could equally as well produce money that was a credit to the taxpayer.[78]

He thought at length about the subject of money over 1921 and 1922. In May 1922, he published a proposal, entitled "A Proposed Amendment to the Federal Reserve Banking System".[79] In it, he detailed an explanation of a commodity backed currency, in which the Federal Reserve would issue interest-free currency to farmers, based on the value of commodities they produced. During a publicity tour that he took with friend and fellow inventor, Henry Ford, he spoke publicly about his desire for monetary reform. For insight, he corresponded with prominent academic and banking professionals. In the end, however, Edison's proposals failed to find support, and were eventually abandoned.[80][81]

In 1887, Edison won the Matteucci Medal. In 1890, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The Philadelphia City Council named Edison the recipient of the John Scott Medal in 1889.[83]

In 1899, Edison was awarded the Edward Longstreth Medal of The Franklin Institute.[84]

He was named an Honorable Consulting Engineer at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition World's fair in 1904.[83]

In 1908, Edison received the American Association of Engineering Societies John Fritz Medal.[83]

In 1915, Edison was awarded Franklin Medal of The Franklin Institute for discoveries contributing to the foundation of industries and the well-being of the human race.[85]

In 1920, The United States Navy department awarded him the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[83]

In 1923, The American Institute of Electrical Engineers created the Edison Medal and he was its first recipient.[83]

In 1927, he was granted membership in the National Academy of Sciences.[83]

On May 29, 1928, Edison received the Congressional Gold Medal.[83]

In 1983, the United States Congress, pursuant to Senate Joint Resolution 140 (Public Law 97—198), designated February 11, Edison's birthday, as National Inventor's Day.[86]

Edison was ranked thirty-fifth on Michael H. Hart's 1978 book The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, a list of the most influential figures in history.[87] Life magazine (USA), in a special double issue in 1997, placed Edison first in the list of the "100 Most Important People in the Last 1000 Years", noting that the light bulb he promoted "lit up the world". In the 2005 television series The Greatest American, he was voted by viewers as the fifteenth-greatest.

In 2008, Edison was inducted in the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

In 2010, Edison was honored with a Technical Grammy Award.

In 2011, Edison was inducted into the Entrepreneur Walk of Fame, and named a Great Floridian by the Florida Governor and Cabinet.[88]

In 1883, the City Hotel in Sunbury, Pennsylvania was the first building to be lit with Edison's three-wire system. The hotel was renamed The Hotel Edison upon Edison's return to the City on 1922.[90]

Lake Thomas A Edison in California was named after Edison to mark the 75th anniversary of the incandescent light bulb.[91]

Edison was on hand to turn on the lights at the Hotel Edison in New York City when it opened in 1931.[92]

Three bridges around the United States have been named in Edison's honor: the Edison Bridge in New Jersey,[93] the Edison Bridge in Florida,[94] and the Edison Bridge in Ohio.[95]

In space, his name is commemorated in asteroid 742 Edisona.

In Detroit, the Edison Memorial Fountain in Grand Circus Park was created to honor his achievements. The limestone fountain was dedicated October 21, 1929, the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of the lightbulb.[100] On the same night, The Edison Institute was dedicated in nearby Dearborn.

In the Netherlands, the major music awards are named the Edison Award after him. The award is an annual Dutch music prize, awarded for outstanding achievements in the music industry, and is one of the oldest music awards in the world, having been presented since 1960.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers concedes the Thomas A. Edison Patent Award to individual patents since 2000.[101]

On February 11, 2011, on Thomas Edison's 164th birthday, Google's homepage featured an animated Google Doodle commemorating his many inventions. When the cursor was hovered over the doodle, a series of mechanisms seemed to move, causing a lightbulb to glow.[102]

Source: Wikipedia

Edison is the fourth most prolific inventor in history, holding 1,093 US patents in his name, as well as many patents in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. He is credited with numerous inventions that contributed to mass communication and, in particular, telecommunications. These included a stock ticker, a mechanical vote recorder, a battery for an electric car, electrical power, recorded music and motion pictures.

His advanced work in these fields was an outgrowth of his early career as a telegraph operator. Edison developed a system of electric-power generation and distribution[3] to homes, businesses, and factories – a crucial development in the modern industrialized world. His first power station was on Pearl Street in Manhattan, New York.[3]

Early life

Thomas Edison was born in Milan, Ohio, and grew up in Port Huron, Michigan. He was the seventh and last child of Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr. (1804–96, born in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia, Canada) and Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810–1871, born in Chenango County, New York).[4] His father had to escape from Canada because he took part in the unsuccessful Mackenzie Rebellion of 1837 [5] Edison reported being of Dutch ancestry.[6]In school, the young Edison's mind often wandered, and his teacher, the Reverend Engle, was overheard calling him "addled". This ended Edison's three months of official schooling. Edison recalled later, "My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me; and I felt I had something to live for, someone I must not disappoint." His mother taught him at home.[7] Much of his education came from reading R.G. Parker's School of Natural Philosophy.

Edison developed hearing problems at an early age. The cause of his deafness has been attributed to a bout of scarlet fever during childhood and recurring untreated middle-ear infections. Around the middle of his career, Edison attributed the hearing impairment to being struck on the ears by a train conductor when his chemical laboratory in a boxcar caught fire and he was thrown off the train in Smiths Creek, Michigan, along with his apparatus and chemicals. In his later years, he modified the story to say the injury occurred when the conductor, in helping him onto a moving train, lifted him by the ears.[8][9]

Edison's family moved to Port Huron, Michigan, after the railroad bypassed Milan in 1854 and business declined;[10] his life there was bittersweet. Edison sold candy and newspapers on trains running from Port Huron to Detroit, and sold vegetables to supplement his income. He also studied qualitative analysis, and conducted chemical experiments on the train until an accident prohibited further work of the kind.[11]

Edison obtained the exclusive right to sell newspapers on the road, and, with the aid of four assistants, he set in type and printed the Grand Trunk Herald, which he sold with his other papers.[11] This began Edison's long streak of entrepreneurial ventures, as he discovered his talents as a businessman. These talents eventually led him to found 14 companies, including General Electric, which is still one of the largest publicly traded companies in the world.[12][13]

Telegrapher

Edison became a telegraph operator after he saved three-year-old Jimmie MacKenzie from being struck by a runaway train. Jimmie's father, station agent J.U. MacKenzie of Mount Clemens, Michigan, was so grateful that he trained Edison as a telegraph operator. Edison's first telegraphy job away from Port Huron was at Stratford Junction, Ontario, on the Grand Trunk Railway.[14]In 1866, at the age of 19, Edison moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where, as an employee of Western Union, he worked the Associated Press bureau news wire. Edison requested the night shift, which allowed him plenty of time to spend at his two favorite pastimes—reading and experimenting. Eventually, the latter pre-occupation cost him his job. One night in 1867, he was working with a lead–acid battery when he spilled sulfuric acid onto the floor. It ran between the floorboards and onto his boss's desk below. The next morning Edison was fired.[15]

One of his mentors during those early years was a fellow telegrapher and inventor named Franklin Leonard Pope, who allowed the impoverished youth to live and work in the basement of his Elizabeth, New Jersey home. Some of Edison's earliest inventions were related to telegraphy, including a stock ticker. His first patent was for the electric vote recorder, (U.S. Patent 90,646),[16] which was granted on June 1, 1869.[17]

Marriages and children

On December 25, 1871, Edison married 16-year-old Mary Stilwell (1855–1884), whom he had met two months earlier; she was an employee at one of his shops. They had three children:- Marion Estelle Edison (1873–1965), nicknamed "Dot"[18]

- Thomas Alva Edison, Jr. (1876–1935), nicknamed "Dash"[19]

- William Leslie Edison (1878–1937) Inventor, graduate of the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, 1900.[20]

On February 24, 1886, at the age of thirty-nine, Edison married the 20-year-old Mina Miller (1866–1947) in Akron, Ohio.[23] She was the daughter of the inventor Lewis Miller, co-founder of the Chautauqua Institution and a benefactor of Methodist charities. They also had three children together:

- Madeleine Edison (1888–1979), who married John Eyre Sloane.[24][25]

- Charles Edison (1890–1969), Governor of New Jersey (1941 – 1944), and took over his father's company and experimental laboratories upon his father's death.[26]

- Theodore Edison (1898–1992), (MIT Physics 1923), credited with more than 80 patents.

Beginning his career

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

His first phonograph recorded on tinfoil around a grooved cylinder, but had poor sound quality and the recordings could be played only a few times. In the 1880s, a redesigned model using wax-coated cardboard cylinders was produced by Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, and Charles Tainter. This was one reason that Thomas Edison continued work on his own "Perfected Phonograph."

Menlo Park

Edison's Menlo Park Laboratory, removed to Greenfield Village at Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. (Note the organ against the back wall)

The quadruplex telegraph was Edison's first big financial success, and Menlo Park became the first institution set up with the specific purpose of producing constant technological innovation and improvement. Edison was legally attributed with most of the inventions produced there, though many employees carried out research and development under his direction. His staff was generally told to carry out his directions in conducting research, and he drove them hard to produce results.

William Joseph Hammer, a consulting electrical engineer, began his duties as a laboratory assistant to Edison in December 1879. He assisted in experiments on the telephone, phonograph, electric railway, iron ore separator, electric lighting, and other developing inventions. However, Hammer worked primarily on the incandescent electric lamp and was put in charge of tests and records on that device. In 1880, he was appointed chief engineer of the Edison Lamp Works. In his first year, the plant under General Manager Francis Robbins Upton turned out 50,000 lamps. According to Edison, Hammer was "a pioneer of incandescent electric lighting".[31] Frank J. Sprague, a competent mathematician and former naval officer, was recruited by Edward H. Johnson and joined the Edison organization in 1883. One of Sprague's contributions to the Edison Laboratory at Menlo Park was to expand Edison's mathematical methods. Despite the common belief that Edison did not use mathematics, analysis of his notebooks reveal that he was an astute user of mathematical analysis conducted by his assistants such as Francis Robbins Upton, for example, determining the critical parameters of his electric lighting system including lamp resistance by an analysis of Ohm's Law, Joule's Law and economics.[32]

Nearly all of Edison's patents were utility patents, which were protected for a 17-year period and included inventions or processes that are electrical, mechanical, or chemical in nature. About a dozen were design patents, which protect an ornamental design for up to a 14-year period. As in most patents, the inventions he described were improvements over prior art. The phonograph patent, in contrast, was unprecedented as describing the first device to record and reproduce sounds.[33]

In just over a decade, Edison's Menlo Park laboratory had expanded to occupy two city blocks. Edison said he wanted the lab to have "a stock of almost every conceivable material".[34] A newspaper article printed in 1887 reveals the seriousness of his claim, stating the lab contained "eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels ... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark's teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell ... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock's tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores ..." and the list goes on.[35]

Over his desk, Edison displayed a placard with Sir Joshua Reynolds' famous quotation: "There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.[36] This slogan was reputedly posted at several other locations throughout the facility.

With Menlo Park, Edison had created the first industrial laboratory concerned with creating knowledge and then controlling its application.[37]

Carbon telephone transmitter

In 1877–78, Edison invented and developed the carbon microphone used in all telephones along with the Bell receiver until the 1980s. After protracted patent litigation, in 1892 a federal court ruled that Edison and not Emile Berliner was the inventor of the carbon microphone. The carbon microphone was also used in radio broadcasting and public address work through the 1920s.Electric light

Main article: History of the light bulb

After many experiments with platinum and other metal filaments, Edison returned to a carbon filament.[inconsistent] The first successful test was on October 22, 1879;[41] it lasted 13.5 hours.[42] Edison continued to improve this design and by November 4, 1879, filed for U.S. patent 223,898 (granted on January 27, 1880) for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires".[43]

Although the patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament including "cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways",[43] it was not until several months after the patent was granted that Edison and his team discovered a carbonized bamboo filament that could last over 1,200 hours. The idea of using this particular raw material originated from Edison's recalling his examination of a few threads from a bamboo fishing pole while relaxing on the shore of Battle Lake in the present-day state of Wyoming, where he and other members of a scientific team had traveled so that they could clearly observe a total eclipse of the sun on July 29, 1878, from the Continental Divide.[44]

In 1878, Edison formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Edison made the first public demonstration of his incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. It was during this time that he said: "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles."[45]

Lewis Latimer joined the Edison Electric Light Company in 1884. Latimer had received a patent in January 1881 for the "Process of Manufacturing Carbons", an improved method for the production of carbon filaments for lightbulbs. Latimer worked as an engineer, a draftsman and an expert witness in patent litigation on electric lights.[46]

George Westinghouse's company bought Philip Diehl's competing induction lamp patent rights (1882) for $25,000, forcing the holders of the Edison patent to charge a more reasonable rate for the use of the Edison patent rights and lowering the price of the electric lamp.[47]

On October 8, 1883, the US patent office ruled that Edison's patent was based on the work of William Sawyer and was therefore invalid. Litigation continued for nearly six years, until October 6, 1889, when a judge ruled that Edison's electric-light improvement claim for "a filament of carbon of high resistance" was valid.[48] To avoid a possible court battle with Joseph Swan, whose British patent had been awarded a year before Edison's, he and Swan formed a joint company called Ediswan to manufacture and market the invention in Britain.

Mahen Theatre in Brno (in what is now the Czech Republic) was the first public building in the world to use Edison's electric lamps, with the installation supervised by Edison's assistant in the invention of the lamp, Francis Jehl.[49] In September 2010, a sculpture of three giant light bulbs was erected in Brno, in front of the theatre.[50]

Electric power distribution

Edison patented a system for electricity distribution in 1880, which was essential to capitalize on the invention of the electric lamp. On December 17, 1880, Edison founded the Edison Illuminating Company. The company established the first investor-owned electric utility in 1882 on Pearl Street Station, New York City. It was on September 4, 1882, that Edison switched on his Pearl Street generating station's electrical power distribution system, which provided 110 volts direct current (DC) to 59 customers in lower Manhattan.[51]Earlier in the year, in January 1882, he had switched on the first steam-generating power station at Holborn Viaduct in London. The DC supply system provided electricity supplies to street lamps and several private dwellings within a short distance of the station. On January 19, 1883, the first standardized incandescent electric lighting system employing overhead wires began service in Roselle, New Jersey.

Nikola Tesla worked for Edison for two years at the Continental Edison Company in France starting in 1882,[52] and another year at the Edison Machine Works in New York City[53] ending in a disagreement over pay.

War of currents

Main article: War of Currents

Extravagant displays of electric lights quickly became a feature of public events, as in this picture from the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition.

In 1887, there were 121 Edison power stations in the United States delivering DC electricity to customers. When the limitations of DC were discussed by the public, Edison launched a propaganda campaign to convince people that AC was far too dangerous to use. The problem with DC was that the power plants could economically deliver DC electricity only to customers within about one and a half miles (about 2.4 km) from the generating station, so that it was suitable only for central business districts. When George Westinghouse suggested using high-voltage AC instead, as it could carry electricity hundreds of miles with marginal loss of power, Edison waged a "War of Currents" to prevent AC from being adopted.

The war against AC led him to become involved in the development and promotion of the electric chair (using AC) as an attempt to portray AC to have greater lethal potential than DC. Edison went on to carry out a brief but intense campaign to ban the use of AC or to limit the allowable voltage for safety purposes. As part of this campaign, Edison's employees publicly electrocuted stray or unwanted animals to demonstrate the dangers of AC;[54][55] alternating electric currents are slightly more dangerous in that frequencies near 60 Hz have a markedly greater potential for inducing fatal "cardiac fibrillation" than do direct currents.[56] On one of the more notable occasions, in 1903, Edison's workers electrocuted Topsy the elephant at Luna Park, near Coney Island, after she had killed several men and her owners wanted her put to death.[57] His company filmed the electrocution.

AC replaced DC in most instances of generation and power distribution, enormously extending the range and improving the efficiency of power distribution. Though widespread use of DC ultimately lost favor for distribution, it exists today primarily in long-distance high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission systems. Low-voltage DC distribution continued to be used in high-density downtown areas for many years but was eventually replaced by AC low-voltage network distribution in many of them.[58]

DC had the advantage that large battery banks could maintain continuous power through brief interruptions of the electric supply from generators and the transmission system. Utilities such as Commonwealth Edison in Chicago had rotary converters or motor-generator sets, which could change DC to AC and AC to various frequencies in the early to mid-20th century. Utilities supplied rectifiers to convert the low voltage AC to DC for such DC loads as elevators, fans and pumps. There were still 1,600 DC customers in downtown New York City as of 2005, and service was finally discontinued only on November 14, 2007.[58] Most subway systems are still powered by direct current.

Other inventions and projects

Fluoroscopy

Edison is credited with designing and producing the first commercially available fluoroscope, a machine that uses X-rays to take radiographs. Until Edison discovered that calcium tungstate fluoroscopy screens produced brighter images than the barium platinocyanide screens originally used by Wilhelm Röntgen, the technology was capable of producing only very faint images.The fundamental design of Edison's fluoroscope is still in use today, although Edison himself abandoned the project after nearly losing his own eyesight and seriously injuring his assistant, Clarence Dally. Dally had made himself an enthusiastic human guinea pig for the fluoroscopy project and in the process been exposed to a poisonous dose of radiation. He later died of injuries related to the exposure. In 1903, a shaken Edison said "Don't talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them."[59]

Media inventions

The key to Edison's fortunes was telegraphy. With knowledge gained from years of working as a telegraph operator, he learned the basics of electricity. This allowed him to make his early fortune with the stock ticker, the first electricity-based broadcast system. Edison patented the sound recording and reproducing phonograph in 1878. Edison was also granted a patent for the motion picture camera or "Kinetograph". He did the electromechanical design, while his employee W.K.L. Dickson, a photographer, worked on the photographic and optical development. Much of the credit for the invention belongs to Dickson.[41] In 1891, Thomas Edison built a Kinetoscope, or peep-hole viewer. This device was installed in penny arcades, where people could watch short, simple films. The kinetograph and kinetoscope were both first publicly exhibited May 20, 1891.[60]On August 9, 1892, Edison received a patent for a two-way telegraph. In April 1896, Thomas Armat's Vitascope, manufactured by the Edison factory and marketed in Edison's name, was used to project motion pictures in public screenings in New York City. Later he exhibited motion pictures with voice soundtrack on cylinder recordings, mechanically synchronized with the film.

The June 1894 Leonard–Cushing bout. Each of the six one-minute rounds

recorded by the Kinetoscope was made available to exhibitors for $22.50.[61] Customers who watched the final round saw Leonard score a knockdown.

The first kinetoscopes arrived in Belgium at the Fairs in early 1895. The Edison's Kinétoscope Français, a Belgian company, was founded in Brussels on January 15, 1895, with the rights to sell the kinetoscopes in Monaco, France and the French colonies. The main investors in this company were Belgian industrialists.[63]

On May 14, 1895, the Edison's Kinétoscope Belge was founded in Brussels. The businessman Ladislas-Victor Lewitzki, living in London but active in Belgium and France, took the initiative in starting this business. He had contacts with Leon Gaumont and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. In 1898 he also became a shareholder of the Biograph and Mutoscope Company for France.[63]

In 1901, he visited the Sudbury area in Ontario, Canada, as a mining prospector, and is credited with the original discovery of the Falconbridge ore body. His attempts to mine the ore body were not successful, however, and he abandoned his mining claim in 1903.[64] A street in Falconbridge, as well as the Edison Building, which served as the head office of Falconbridge Mines, are named for him.

Other exhibitors similarly routinely copied and exhibited each other's films.[65] To better protect the copyrights on his films, Edison deposited prints of them on long strips of photographic paper with the U.S. copyright office. Many of these paper prints survived longer and in better condition than the actual films of that era.[66]

Edison's favorite movie was The Birth of a Nation. He thought that talkies had "spoiled everything" for him. "There isn't any good acting on the screen. They concentrate on the voice now and have forgotten how to act. I can sense it more than you because I am deaf."[67] His favorite stars were Mary Pickford and Clara Bow.[68]

In 1908, Edison started the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was a conglomerate of nine major film studios (commonly known as the Edison Trust). Thomas Edison was the first honorary fellow of the Acoustical Society of America, which was founded in 1929.

West Orange and Fort Myers (1886–1931)

Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone, respectively. Ft. Myers, Florida, February 11, 1929

Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, later lived a few hundred feet away from Edison at his winter retreat in Fort Myers, Florida. Edison even contributed technology to the automobile. They were friends until Edison's death.

In 1928, Edison joined the Fort Myers Civitan Club. He believed strongly in the organization, writing that "The Civitan Club is doing things—big things—for the community, state, and nation, and I certainly consider it an honor to be numbered in its ranks."[69] He was an active member in the club until his death, sometimes bringing Henry Ford to the club's meetings.

Final years and death

Edison was active in business right up to the end. Just months before his death, the Lackawanna Railroad inaugurated suburban electric train service from Hoboken to Montclair, Dover, and Gladstone in New Jersey. Electrical transmission for this service was by means of an overhead catenary system using direct current, which Edison had championed. Despite his frail condition, Edison was at the throttle of the first electric MU (Multiple-Unit) train to depart Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken in September 1930, driving the train the first mile through Hoboken yard on its way to South Orange.[70]This fleet of cars would serve commuters in northern New Jersey for the next 54 years until their retirement in 1984. A plaque commemorating Edison's inaugural ride can be seen today in the waiting room of Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken, which is presently operated by New Jersey Transit.[70]

Edison was said to have been influenced by a popular fad diet in his last few years; "the only liquid he consumed was a pint of milk every three hours".[41] He is reported to have believed this diet would restore his health. However, this tale is doubtful. In 1930, the year before Edison died, Mina said in an interview about him, "correct eating is one of his greatest hobbies." She also said that during one of his periodic "great scientific adventures", Edison would be up at 7:00, have breakfast at 8:00, and be rarely home for lunch or dinner, implying that he continued to have all three.[67]

Edison became the owner of his Milan, Ohio, birthplace in 1906. On his last visit, in 1923, he was reportedly shocked to find his old home still lit by lamps and candles.

Thomas Edison died of complications of diabetes on October 18, 1931, in his home, "Glenmont" in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey, which he had purchased in 1886 as a wedding gift for Mina. He is buried behind the home.[71][72]

Edison's last breath is reportedly contained in a test tube at the Henry Ford Museum. Ford reportedly convinced Charles Edison to seal a test tube of air in the inventor's room shortly after his death, as a memento. A plaster death mask was also made.[73]

Mina died in 1947.

Views on politics, religion and metaphysics

Historian Paul Israel has characterized Edison as a "freethinker".[41] Edison was heavily influenced by Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason.[41] Edison defended Paine's "scientific deism", saying, "He has been called an atheist, but atheist he was not. Paine believed in a supreme intelligence, as representing the idea which other men often express by the name of deity."[41] In an October 2, 1910, interview in the New York Times Magazine, Edison stated:Nature is what we know. We do not know the gods of religions. And nature is not kind, or merciful, or loving. If God made me — the fabled God of the three qualities of which I spoke: mercy, kindness, love — He also made the fish I catch and eat. And where do His mercy, kindness, and love for that fish come in? No; nature made us — nature did it all — not the gods of the religions.[74]Edison was called an atheist for those remarks, and although he did not allow himself to be drawn into the controversy publicly, he clarified himself in a private letter: "You have misunderstood the whole article, because you jumped to the conclusion that it denies the existence of God. There is no such denial, what you call God I call Nature, the Supreme intelligence that rules matter. All the article states is that it is doubtful in my opinion if our intelligence or soul or whatever one may call it lives hereafter as an entity or disperses back again from whence it came, scattered amongst the cells of which we are made."[41]

Nonviolence was key to Edison's moral views, and when asked to serve as a naval consultant for World War I, he specified he would work only on defensive weapons and later noted, "I am proud of the fact that I never invented weapons to kill." Edison's philosophy of nonviolence extended to animals as well, about which he stated: "Nonviolence leads to the highest ethics, which is the goal of all evolution. Until we stop harming all other living beings, we are still savages."[75] However, he is also notorious for having electrocuted a number of dogs in 1888, both by direct and alternating current, in an attempt to argue that the former (which he had a vested business interest in promoting) was safer than the latter (favored by his rival George Westinghouse).[76]

Edison's success in promoting direct current as less lethal also led to alternating current being used in the electric chair adopted by New York in 1889 as a supposedly humane execution method. Because Westinghouse was angered by the decision, he funded Eighth Amendment-based appeals for inmates set to die in the electric chair, ultimately resulting in Edison providing the generators which powered early electrocutions and testifying successfully on behalf of the state that electrocution was a painless method of execution.[77]

Views on money

Thomas Edison was an advocate for monetary reform in the United States. He was ardently opposed to the gold standard, and debt based money. Famously, he was quoted in the New York Times stating "Gold is a relic of Julius Caesar, and interest is an invention of Satan."[78]In the same article, he expounded upon the absurdity of a monetary system in which the taxpayer of the United States, in need of a loan, be compelled to pay in return perhaps double the principal, or even greater sums, due to interest. His basic point was that if the Government can produce debt based money, it could equally as well produce money that was a credit to the taxpayer.[78]

He thought at length about the subject of money over 1921 and 1922. In May 1922, he published a proposal, entitled "A Proposed Amendment to the Federal Reserve Banking System".[79] In it, he detailed an explanation of a commodity backed currency, in which the Federal Reserve would issue interest-free currency to farmers, based on the value of commodities they produced. During a publicity tour that he took with friend and fellow inventor, Henry Ford, he spoke publicly about his desire for monetary reform. For insight, he corresponded with prominent academic and banking professionals. In the end, however, Edison's proposals failed to find support, and were eventually abandoned.[80][81]

Awards

The President of the Third French Republic, Jules Grévy, on the recommendation of his Minister of Foreign Affairs Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire and with the presentations of the Minister of Posts and Telegraphs Louis Cochery, designated Edison with the distinction of an 'Officer of the Legion of Honour' (Légion d'honneur) by decree on November 10, 1881;[82] He also named a Chevalier in 1879, and a Commander in 1889.[83]In 1887, Edison won the Matteucci Medal. In 1890, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The Philadelphia City Council named Edison the recipient of the John Scott Medal in 1889.[83]

In 1899, Edison was awarded the Edward Longstreth Medal of The Franklin Institute.[84]

He was named an Honorable Consulting Engineer at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition World's fair in 1904.[83]

In 1908, Edison received the American Association of Engineering Societies John Fritz Medal.[83]

In 1915, Edison was awarded Franklin Medal of The Franklin Institute for discoveries contributing to the foundation of industries and the well-being of the human race.[85]

In 1920, The United States Navy department awarded him the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[83]

In 1923, The American Institute of Electrical Engineers created the Edison Medal and he was its first recipient.[83]

In 1927, he was granted membership in the National Academy of Sciences.[83]

On May 29, 1928, Edison received the Congressional Gold Medal.[83]

In 1983, the United States Congress, pursuant to Senate Joint Resolution 140 (Public Law 97—198), designated February 11, Edison's birthday, as National Inventor's Day.[86]

Edison was ranked thirty-fifth on Michael H. Hart's 1978 book The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, a list of the most influential figures in history.[87] Life magazine (USA), in a special double issue in 1997, placed Edison first in the list of the "100 Most Important People in the Last 1000 Years", noting that the light bulb he promoted "lit up the world". In the 2005 television series The Greatest American, he was voted by viewers as the fifteenth-greatest.

In 2008, Edison was inducted in the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

In 2010, Edison was honored with a Technical Grammy Award.

In 2011, Edison was inducted into the Entrepreneur Walk of Fame, and named a Great Floridian by the Florida Governor and Cabinet.[88]

Tributes

Places and people named for Edison

Several places have been named after Edison, most notably the town of Edison, New Jersey. Thomas Edison State College, a nationally known college for adult learners, is in Trenton, New Jersey. Two community colleges are named for him: Edison State College in Fort Myers, Florida, and Edison Community College in Piqua, Ohio.[89] There are numerous high schools named after Edison (see Edison High School) and other schools including Thomas A. Edison Middle School.In 1883, the City Hotel in Sunbury, Pennsylvania was the first building to be lit with Edison's three-wire system. The hotel was renamed The Hotel Edison upon Edison's return to the City on 1922.[90]

Lake Thomas A Edison in California was named after Edison to mark the 75th anniversary of the incandescent light bulb.[91]

Edison was on hand to turn on the lights at the Hotel Edison in New York City when it opened in 1931.[92]

Three bridges around the United States have been named in Edison's honor: the Edison Bridge in New Jersey,[93] the Edison Bridge in Florida,[94] and the Edison Bridge in Ohio.[95]

In space, his name is commemorated in asteroid 742 Edisona.

Museums and memorials

In West Orange, New Jersey, the 13.5 acre (5.5 ha) Glenmont estate is maintained and operated by the National Park Service as the Edison National Historic Site.[96] The Thomas Alva Edison Memorial Tower and Museum is in the town of Edison, New Jersey.[97] In Beaumont, Texas, there is an Edison Museum, though Edison never visited there.[98] The Port Huron Museum, in Port Huron, Michigan, restored the original depot that Thomas Edison worked out of as a young newsbutcher. The depot has been named the Thomas Edison Depot Museum.[99] The town has many Edison historical landmarks, including the graves of Edison's parents, and a monument along the St. Clair River. Edison's influence can be seen throughout this city of 32,000.In Detroit, the Edison Memorial Fountain in Grand Circus Park was created to honor his achievements. The limestone fountain was dedicated October 21, 1929, the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of the lightbulb.[100] On the same night, The Edison Institute was dedicated in nearby Dearborn.

Companies bearing Edison's name

- Edison General Electric, merged with Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric

- Commonwealth Edison, now part of Exelon

- Consolidated Edison

- Edison International

- Detroit Edison, a unit of DTE Energy

- Edison S.p.A., a unit of Italenergia

- Trade association the Edison Electric Institute, a lobbying and research group for investor-owned utilities in the United States

- Edison Ore-Milling Company

- Edison Portland Cement Company

Awards named in honor of Edison

The Edison Medal was created on February 11, 1904, by a group of Edison's friends and associates. Four years later the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE), later IEEE, entered into an agreement with the group to present the medal as its highest award. The first medal was presented in 1909 to Elihu Thomson. It is the oldest award in the area of electrical and electronics engineering, and is presented annually "for a career of meritorious achievement in electrical science, electrical engineering or the electrical arts."In the Netherlands, the major music awards are named the Edison Award after him. The award is an annual Dutch music prize, awarded for outstanding achievements in the music industry, and is one of the oldest music awards in the world, having been presented since 1960.

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers concedes the Thomas A. Edison Patent Award to individual patents since 2000.[101]

Other items named after Edison

The United States Navy named the USS Edison (DD-439), a Gleaves class destroyer, in his honor in 1940. The ship was decommissioned a few months after the end of World War II. In 1962, the Navy commissioned USS Thomas A. Edison (SSBN-610), a fleet ballistic missile nuclear-powered submarine.In popular culture

Main article: Thomas Edison in popular culture

Thomas Edison has appeared in popular culture

as a character in novels, films, comics and video games. His prolific

inventing helped make him an icon and he has made appearances in popular

culture during his lifetime down to the present day. His is also

portrayed in popular culture as an adversary of Nikola Tesla.On February 11, 2011, on Thomas Edison's 164th birthday, Google's homepage featured an animated Google Doodle commemorating his many inventions. When the cursor was hovered over the doodle, a series of mechanisms seemed to move, causing a lightbulb to glow.[102]

See also

- Animated Hero Classics – an animated DVD biography series of historical figures, including Thomas Edison

- Edison Pioneers - a group formed in 1918 by employees and other associates of Thomas Edison

- John I. Beggs

- Joseph Swan

- List of Edison patents

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- Phonomotor

- Thomas Alva Edison Birthplace

- Thomas E. Murray

- Thomas Edison National Historical Park

- Yoshiro Okabe

- Edwin Stanton Porter

References

- ^ a b "The Wizard of Menlo Park". The Franklin Institute. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan. "The Electrifying Edison." Web: Time July 5, 2010

- ^ a b "Con Edison: A Brief History of Con Edison - electricity". Coned.com. January 1, 1998. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ National Historic Landmarks Program (NHL)

- ^ "Samuel and Nancy Elliott Edison". National Park Service. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Baldwin, Neal (1995). Edison: Inventing the Century. Hyperion. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-7868-6041-8.

- ^ "Edison Family Album". US National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ^ "Edison" by Matthew Josephson. McGraw Hill, New York, 1959, ISBN 978-0-07-033046-7

- ^ "Edison: Inventing the Century" by Neil Baldwin, University of Chicago Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-226-03571-0

- ^ Josephson, p 18

- ^ a b

"Edison, Thomas Alva". The Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1918.

"Edison, Thomas Alva". The Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1918. - ^ "GE emerges world's largest company: Forbes". Trading Markets.com. April 10, 2009. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ "GE emerges world's largest company: Forbes". Indian Express.com. April 9, 2009. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Baldwin, page 37

- ^ Baldwin, pages 40–41

- ^ "U.S. Patent 90,646". Patimg1.uspto.gov. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ The Edison Papers, Rutgers University. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Baldwin 1995, p.60

- ^ Baldwin 1995, p.67

- ^ "Older Son To Sue To Void Edison Will; William, Second Child Of The Counsel". New York Times. October 31, 1931. "The will of Thomas A. Edison, filed in Newark last Thursday, which leaves the bulk of the inventor's $12 million estate to the sons of his second wife, was attacked as unfair yesterday by William L. Edison, second son of the first wife, who announced at the same time that he would sue to break it."

- ^ "The Life of Thomas Edison", American Memory, Library of Congress, Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ "Thomas Edison’s First Wife May Have Died of a Morphine Overdose", Rutgers Today. Retrieved November 18, 2011

- ^ "Thomas Edison's Children". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. December 16, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "Madeleine Edison a Bride. Inventor's Daughter Married to J. E. Sloan by Mgr. Brann". New York Times. June 18, 1914, Thursday.

- ^ "Mrs. John Eyre Sloane Has a Son at the Harbor Sanitarium Here". New York Times. January 10, 1931, Saturday.

- ^ "Charles Edison, 78, Ex-Governor Of Jersey and U.S. Aide, Is Dead". New York Times. August 1969.

- ^ "Edison's Widow Very III". New York Times. August 21, 1947, Thursday.

- ^ "Rites for Mrs. Edison". New York Times. August 26, 1947, Tuesday.

- ^ "The Life of Thomas A. Edison". The Library of Congress. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Trollinger, Vernon (February 11, 2013). "Happy Birthday, Thomas Edison!". Bounce Energy. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Biographiq (2008). Thomas Edison: Life of an Electrifying Man. Filiquarian Publishing, LLC. p. 9. ISBN 9781599862163.

- ^ "The Thomas A. Edison Papers". Edison.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on July 22, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ Evans, Harold, "They Made America." Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2004. ISBN 978-0-316-27766-2. p. 152.

- ^ Wilson, Wendell E. "Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931)". The Mineralogical Record. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Shulman, Seth (1999). Owning the Future. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 158–160.

- ^ "AERONAUTICS: Real Labor". TIME Magazine. December 8, 1930. Retrieved January 10, 2008).

- ^ Israel, Paul. "Edison’s Laboratory". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "In Our Time Archive: Thomas Edison". BBC Radio 4.

- ^ "Moses G. Farmer, Eliot's Inventor". Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ^ Israel, Paul B. 1998. Edison: A life of invention. New York: John Wiley. 217–218

- ^ a b c d e f g Israel, Paul (2000). Edison: A Life of Invention. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-36270-8.

- ^ "Thomas Edison, Original Letters and Primary Source Documents". Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ^ a b U.S. Patent 0,223,898

- ^ Flannery, L. G. (Pat) (1960). John Hunton's Diary, Volume 3. pp. 68, 69.

- ^ "Keynote Address – Second International ALN1 Conference (PDF)". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010.

- ^ "Lewis Howard Latimer". National Park Service. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ "Diehl's Lamp Hit Edison Monopoly," Elizabeth Daily Journal, Friday Evening, October 25, 1929

- ^ Biographiq (2008). Thomas Edison: Life of an Electrifying Man. Filiquarian Publishing, LLC. p. 15. ISBN 9781599862163.

- ^ "About the Memory of a Theatre". National Theatre Brno. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Sculpture of three giant light bulbs: in memory of Thomas Alva Edison

- ^ A brief history of Con Edison:"Electricity"

- ^ "Nikola Tesla: The Genius Who Lit the World". Top Documentary Films.

- ^ "Coming to America". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "IMDB entry on Electrocuting an Elephant (1903)". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ^ "Wired Magazine: "Jan. 4, 1903: Edison Fries an Elephant to Prove His Point"". January 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ "Electrocution Thresholds for Humans". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Tony Long (January 4, 2008). "Jan. 4, 1903: Edison Fries an Elephant to Prove His Point". AlterNet. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Lee, Jennifer (November 14, 2007). "Off Goes the Power Current Started by Thomas Edison". The New York Times Company. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library: Edison fears the hidden perils of the x-rays. New York Worldb/, August 3, 1903, Durham, NC.

- ^ "History of Edison Motion Pictures". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- ^ Leonard–Cushing fight Part of the Library of Congress/Inventing Entertainment educational website. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ "Martin Loiperdinger. Film & Schokolade. Stollwercks Geschäfte mit lebenden Bildern . KINtop Schriften Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Basel 1999 ISBN 3-87877-764-7 (Buch) ISBN 3-87877-760-4 (Buch und Videocassette)". Victorian-cinema.net. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ a b "Guido Convents, Van Kinetoscoop tot Cafe-Cine de Eerste Jaren van de Film in Belgie, 1894–1908, pp. 33–69. Universitaire Pers Leuven. Leuven: 2000. Guido Convents, "'Edison's Kinetscope in Belgium, or, Scientists, Admirers, Businessmen, Industrialists and Crooks", pp. 249–258. in C. Dupré la Tour, A. Gaudreault, R. Pearson (Ed.) Cinema at the Turn of the Century. Québec, 1999". Imdb.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ "Thomas Edison". Greater Sudbury Heritage Museums. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Siegmund Lubin (1851–1923), Who's Who of Victorian Cinema. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ "History of Edison Motion Pictures: Early Edison Motion Picture Production (1892–1895)", Memory.loc.gov, Library of Congress. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Reader's Digest, March 1930, pp. 1042–1044, "Living With a Genius", condensed from The American Magazine February 1930

- ^ "Edison Wears Silk Nightshirt, Hates Talkies, Writes Wife", Capital Times, October 30, 1930

- ^ Armbrester, Margaret E. (1992). The Civitan Story. Birmingham, AL: Ebsco Media. p. 34.

- ^ a b Holland, Kevin J. (2001). Classic American Railroad Terminals. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0832-5.

- ^ "Thomas Edison Dies in Coma at 84; Family With Him as the End Comes; Inventor Succumbs at 3:24 A.M. After Fight for Life Since He Was Stricken on August 1. World-Wide Tribute Is Paid to Him as a Benefactor of Mankind". New York Times. October 18, 1931. "West Orange, New Jersey, Sunday, October 18, 1931. Thomas Alva Edison died at 3:24 o'clock this morning at his home, Glenmont, in the Llewellyn Park section of this city. The great inventor, the fruits of whose genius so magically transformed the everyday world, was 84 years and 8 months old."

- ^ Benoit, Tod (2003). Where are they buried? How did they die?. Black Dog & Leventhal. p. 560. ISBN 978-1-57912-678-0.

- ^ "Is Thomas Edison's last breath preserved in a test tube in the Henry Ford Museum?", The Straight Dope, September 11, 1987. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ ""No Immortality of the Soul" says Thomas A. Edison. In Fact, He Doesn't Believe There Is a Soul — Human Beings Only an Aggregate of Cells and the Brain Only a Wonderful Machine, Says Wizard of Electricity". New York Times. October 2, 1910, Sunday. "Thomas A. Edison in the following interview for the first time speaks to the public on the vital subjects of the human soul and immortality. It will be bound to be a most fascinating, an amazing statement, from one of the most notable and interesting men of the age ... Nature is what we know. We do not know the gods of religions. And nature is not kind, or merciful, or loving. If God made me — the fabled God of the three qualities of which I spoke: mercy, kindness, love — He also made the fish I catch and eat. And where do His mercy, kindness, and love for that fish come in? No; nature made us — nature did it all — not the gods of the religions."

- ^ Cited in Innovate Like Edison: The Success System of America's Greatest Inventor by Sarah Miller Caldicott, Michael J. Gelb, page 37.

- ^ Jonnes

- ^ Bellis, Mary. "Death, Money, and the History of the Electric Chair". About.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2010. "On January 1, 1889, the world's first electrical execution law went into full effect. Westinghouse protested the decision and refused to sell any AC generators directly to prison authorities. Thomas Edison and Harold Brown provided the AC generators needed for the first working electric chairs. George Westinghouse funded the appeals for the first prisoners sentenced to death by electrocution, made on the grounds that "electrocution was cruel and unusual punishment." Edison and Brown both testified for the state that execution was a quick and painless form of death and the State of New York won the appeals."

- ^ a b "FORD SEES WEALTH IN MUSCLE SHOALS" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Edison, 1922

- ^ 2006, Hammes, D.L. and Wills, D.T.,“Thomas Edison’s Monetary Option”, The Journal of the History of Economic Thought. (Vol. 28, No. 3, September 2006). ISSN 1042-7716., pps. 295-308

- ^ 2012, Hammes, David L., Harvesting Gold: Thomas Edison’s Experiment to Re-Invent American Money, Mahler Publishing.

- ^ NNDB online website. The same decree awarded German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz with the designation of Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor, as well as Alexander Graham Bell. The decree preamble cited "for services provided to the Congress and to the International Electrical Exhibition"

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kennelly, Arthur E. (1932). Biographical Memoir of Thomas Alva Edison. National Academy of Sciences. pp. 300–301.

- ^ "Franklin Laureate Database - Edward Longstreth Medal 1899 Laureates". Franklin Institute. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Thomas Alva Edison - Acknowledgement". The Franklin Institute. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Proclamation 5013 -- National Inventors' Day, 1983". Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Hart, Michael H. (1978). The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History. ISBN 9780806513508.

- ^ "Great Floridian Program". Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Edison Community College (Ohio)". Edison.cc.oh.us. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ^ "The Edison Hotel". City of Sunbury. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Description of the Big Creek System". Southern California Edison. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Hotel Edison. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "The History & Technology of the Edison Bridge & Driscoll Bridge over the Raritan River, New Jersey". New Jersey Department of Transportation. 2003. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Solomon, Irvin D. (2001). Thomas Edison: The Fort Myers Connection. Arcadia Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 9780738513690.